Exploring Zane's Trace

After the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the newly formed United States found itself land rich and needing to fairly divide and sell property it had acquired from England to cover debts accrued during the Revolution. The Ordinance of 1785 gave direction to this endeavor and opened the land west of the Appalachian Mountains to settlers and land buyers. The Northwest Ordinance in 1787 then ordained the country North and East of the Ohio River for self-government. As enticing as this land was to citizens wanting to migrate west to own land priced much lower than land in the eastern states or veterans wanting to claim their military bounty land, the area was mostly inaccessible by any way except for the Ohio River on the south and the unexplored and unpredictable waters of Lake Erie on the north.

As settlements spread westward along the river and its tributaries, the method for delivering the mail to citizens of these settlements left much to be desired. If and when the post was received, it was often waterlogged and/or outdated. Despite the best efforts of the Post Master General, confidence in the Postal Service was compromised and dwindling by the mid 1790's in much of Kentucky and the Northwest Territory. To compound the issue of migration, the extreme difficulty of navigating the uncontrolled waters of the Ohio and its tributaries often resulted in loss of life or possessions.

The Idea

Ebenezer Zane had migrated with his family to an area of Virginia across the Ohio River from Wheeling Creek some years prior in 1770 and via tomahawk claim, owned a large portion of the area south of the river as well as some land on the north bank. Having carved a road through the wilderness between Ft. Pitt (Pittsburg) Pennsylvania and Ft. Fincastle, (later Ft. Henry, then Wheeling) Virginia, he understood how much more accessible and convenient land travel was versus travel on the Ohio River.

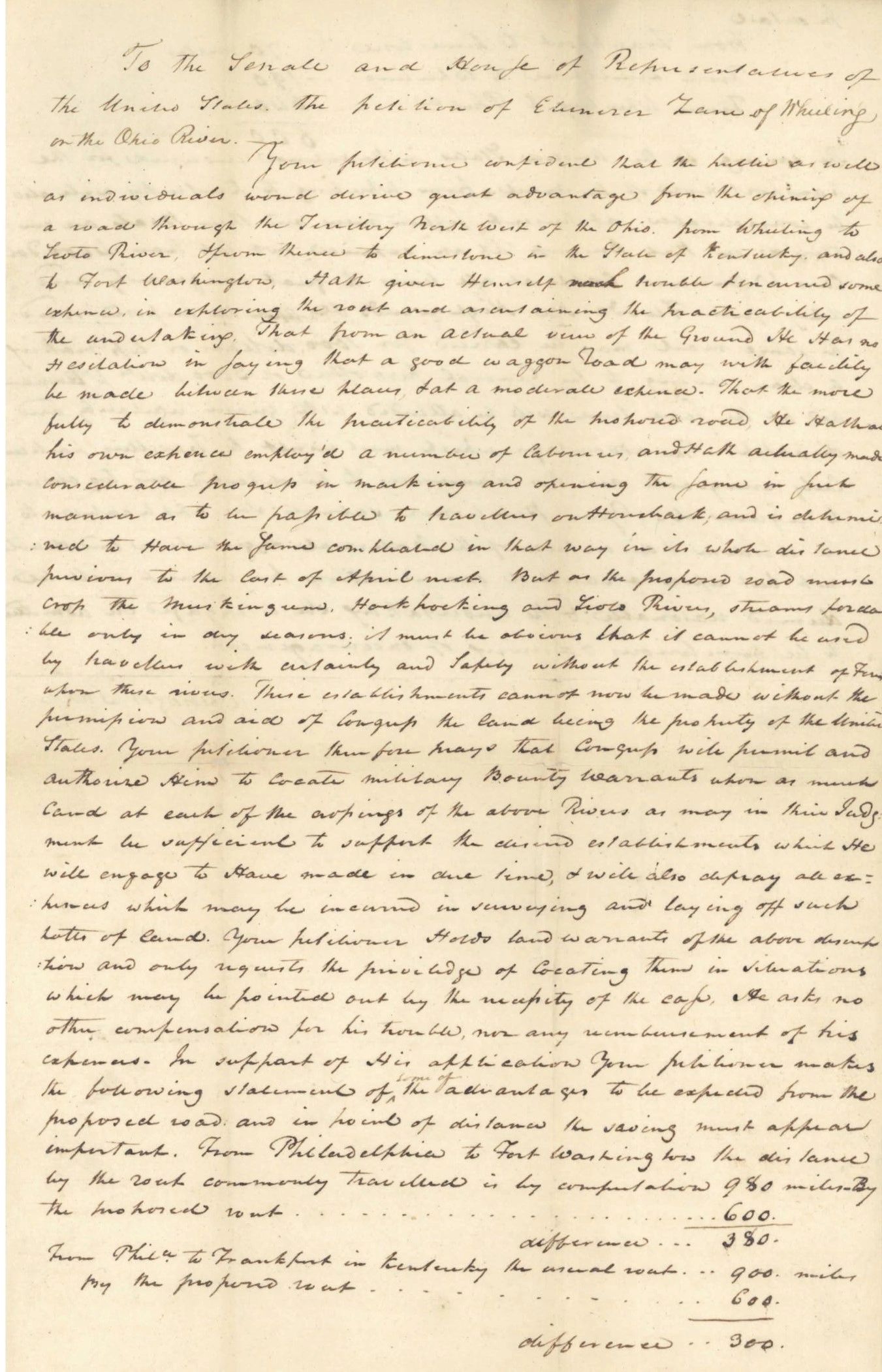

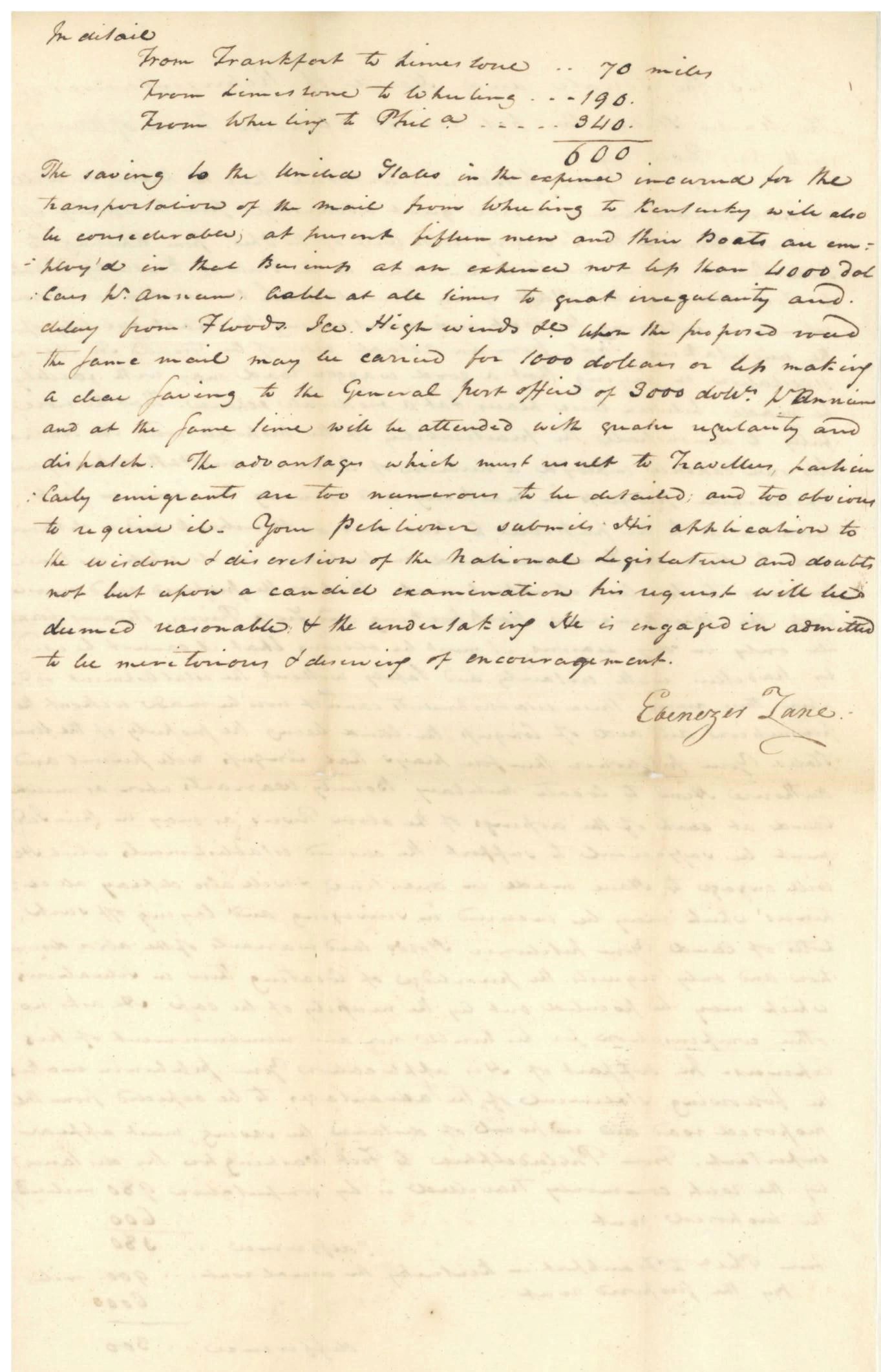

In 1796, Zane petitioned Congress to allow him to build a road with appropriate ferry crossings from Wheeling Virginia (West Virginia) to Limestone (Maysville) KY and pay him in land. Zane pointed out the savings in time and cost of delivering mail by land, showing a potential savings of 75%. He also pointed out the great "advantage to the public as well as individuals" further saying "The advantages which must result to travelers, particularly emigrants are too numerous to be detailed; and too obvious to require it." After being referred to committee, and read before congress three times, an "Act to Authorize Ebenezer Zane to locate certain lands in the Territory of the United States, North West of the River Ohio" was passed on 17 May 1796.

With the help of his brother, Jonathan, whose knowledge of the country was immense due to years of service and exploration in the area, his son-in-law John McIntire, John Green, William McCulloch, Ebenezer Ryan, Joseph Worley, Levi Williams, and an Indian guide, Tomepomehala, the overwhelming task of building the road began. There were undoubtedly others in the corps, forgotten or unmentioned by history. Blazing trees to mark the route and clearing underbrush where it was necessary consumed more than the next year. The "Trace" would not be completed until mid- late 1797, well after the Jan 1797 deadline set by Congress.

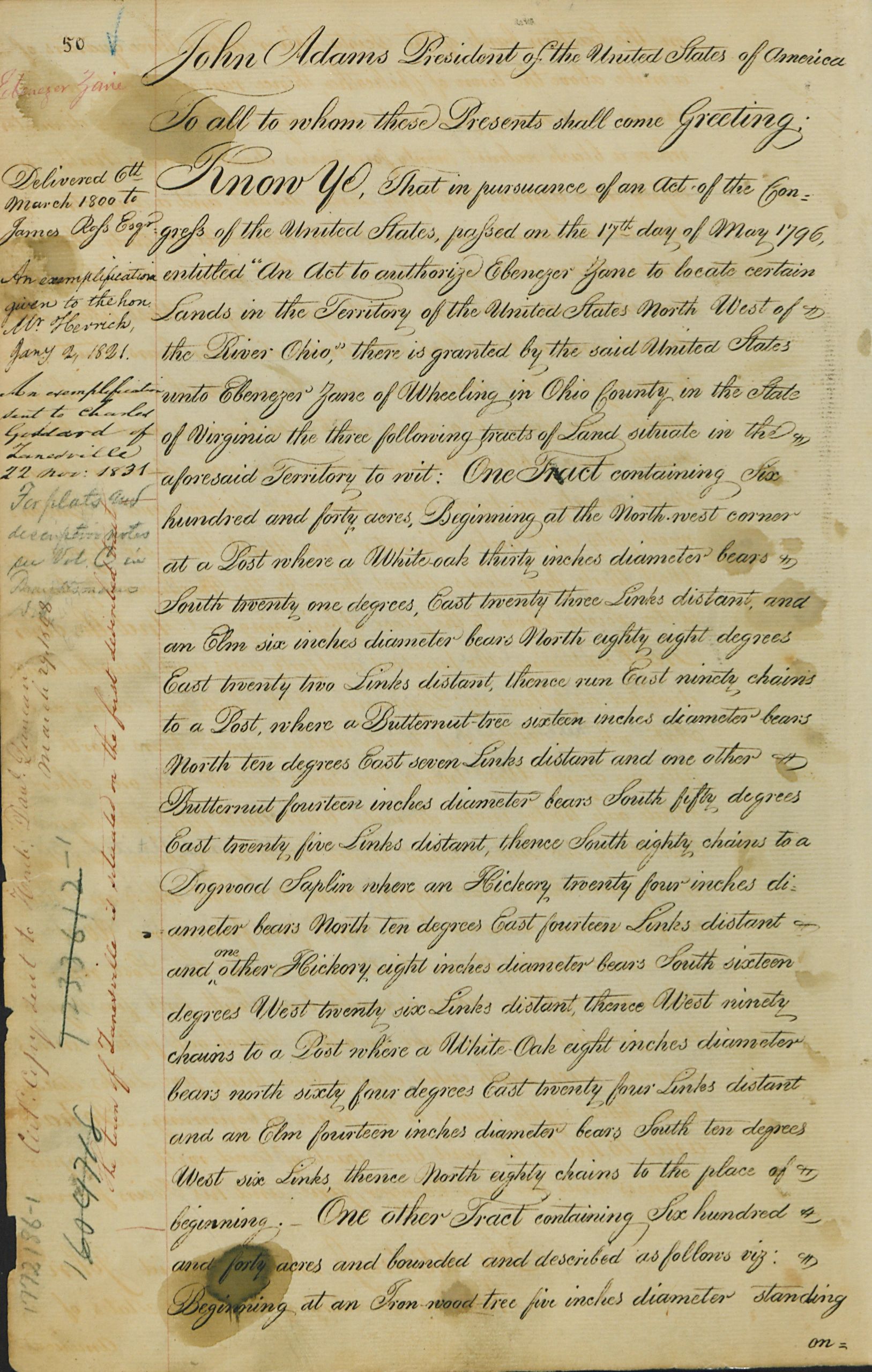

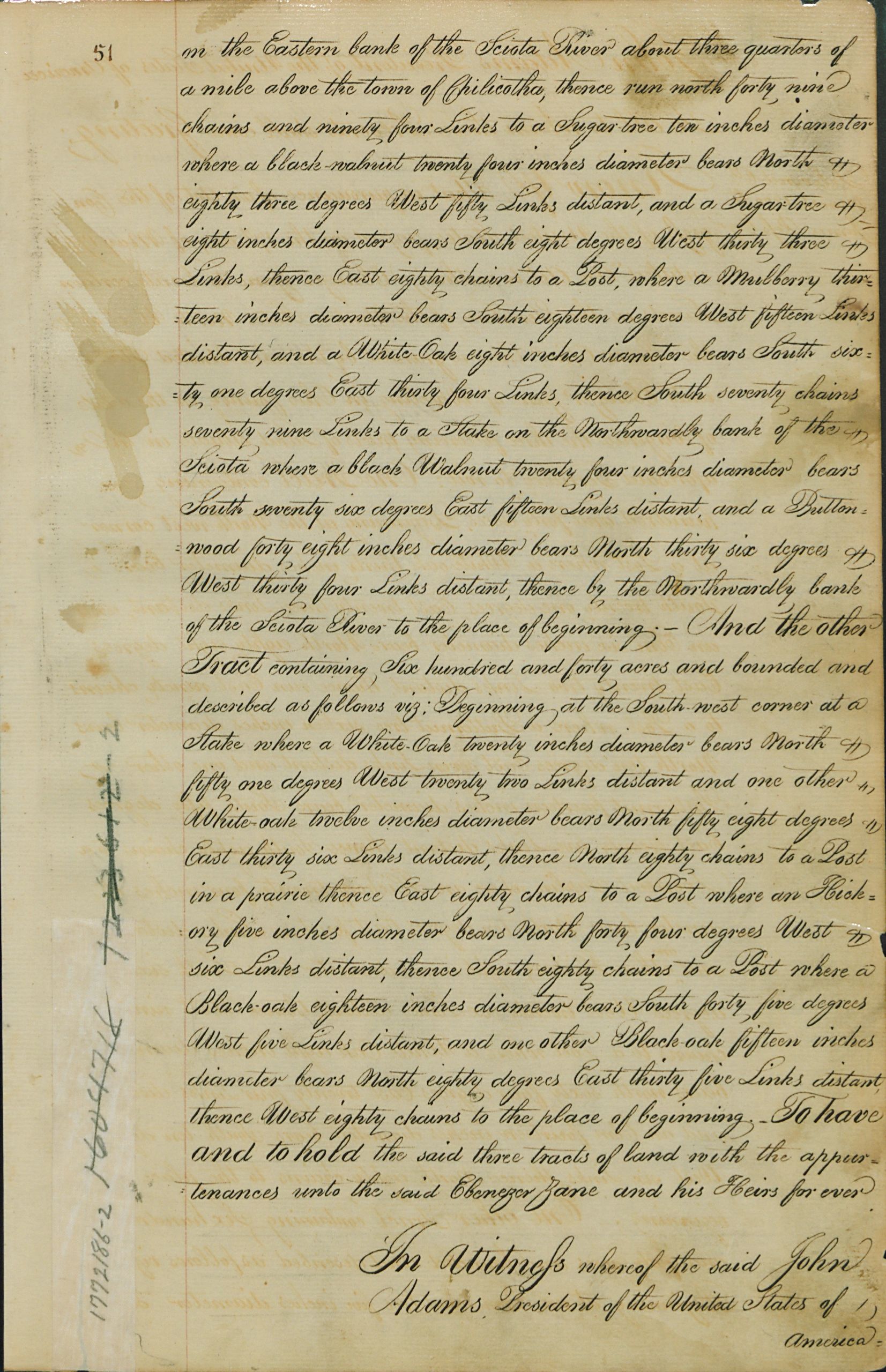

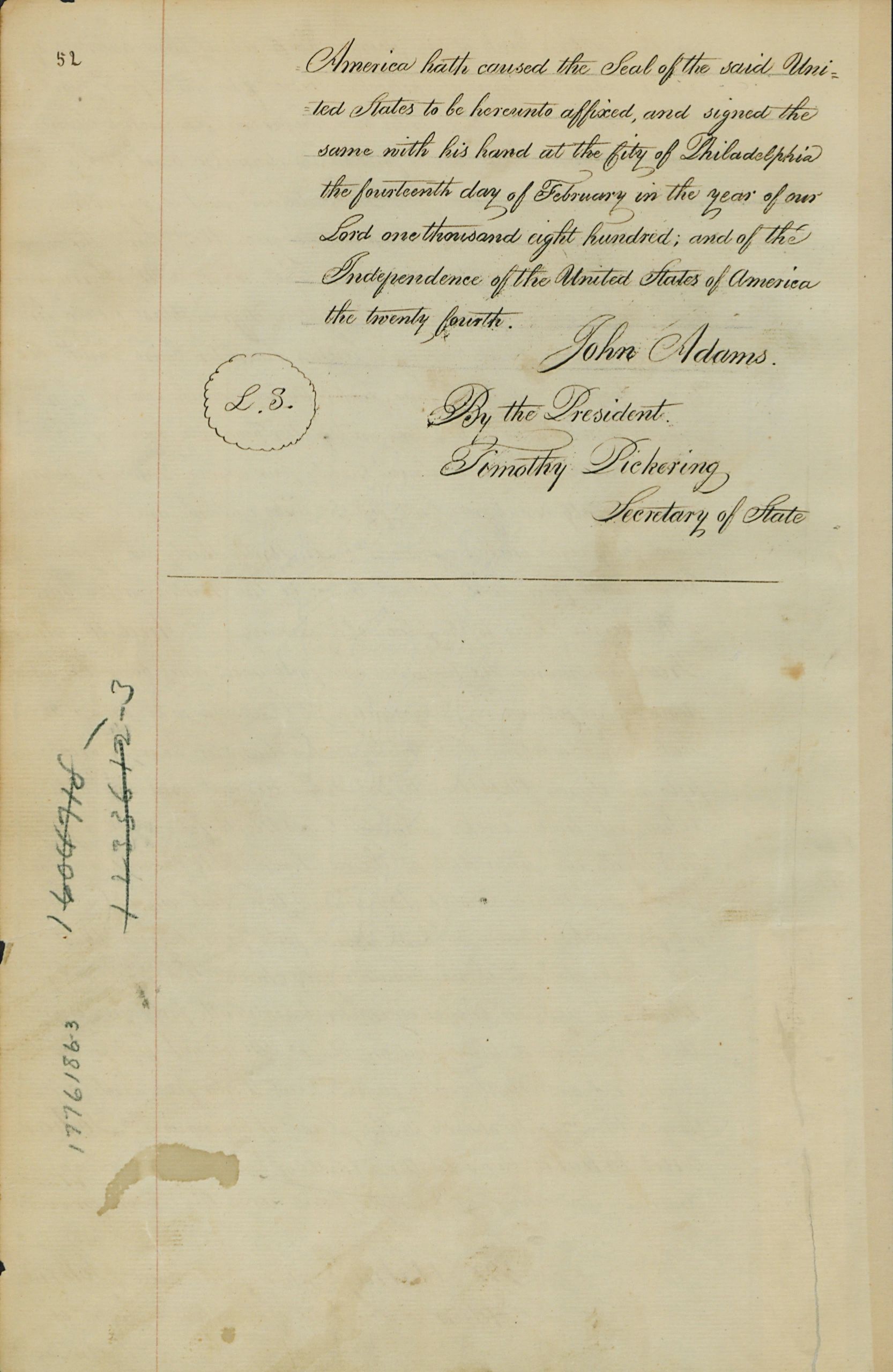

The Trace was never surveyed for just the sake of itself, and completion was disputed at the highest levels of government. Rufus Putnam, the Surveyor General, by January of 1800, confirmed to the Secretary of Treasury that Zane's road was complete to the expectation of the Act to Authorize…, and Patent was issued to Zane on 14 Feb of 1800 for three tracts of land, one each, at the crossing of the Muskingum, Hockhocking, and Scioto Rivers.

The Route

Zane's Trace would originally cross 10 present day counties in Ohio. Beginning in Belmont County across the River Ohio from Wheeling and continue west and southwest through Guernsey, Muskingum, Perry, Fairfield, Pickaway, Ross, Pike, Adams, and finally Brown County on the Ohio River. This road would cross approximately 300 public land entries east of the Scioto River and numerous military warrant claims in the area west of the Scioto.

The most reliable source we have today of the location of the trace are the cadastral survey plats for areas east of the Scioto River. At the time of the survey, three sets of records were made. One set was given to the land office responsible for the district, and the others sent to the U.S. Department of Treasury, at the time responsible for all federal land transactions. One copy was for general use, the second kept as a backup. The backups are mostly missing at this time. As was directed by the Secretary of the Treasury to the Surveyor General, all details of the land were noted and detailed notes were maintained of every survey.

Unfortunately, no such records exist for the area of the Trace west of the Scioto River through the Virginia Military District. The best information we have for this area are derivative (secondary) histories of which often disagree with each other. If compared and analyzed together, enough information can be ascertained to plot Zane's Trace with some reasonable certainty.

Even using a primary record set such as the Cadastral Survey has certain limitations.

While the survey plats and accompanying notes are extremely accurate and are likely to put known points of the trace within eight inches of its location on section lines from marked corners, they do not cover the interior of the sections. The plats indicate a route, often with a dashed line, but these may not truly represent the interior of the section. While it can be presumed that the surveyor likely used the trace for travel and knew its location within the sections, it would be dangerous to make the assumption the interior routes are anything more than the cartographer's best guess.

Life and Travel

In the beginning, Zane's Trace was a far cry from the "wagon road" cited in later historical accounts. Challenges and risk were numerus and inherent on the Trace. Three to five days could be spent crossing the entirety of the road. The early migrants of the Trace saw travel on a trail barely wide enough for horse and rider or pack animal. Assuredly resulting in the unpleasant slap from a low hanging vine or branch, possibly even unseating a distracted rider or loose pack. Of course, the latter would inherently result in spooking the unwary pack animal creating a chaotic mess that may cost hours in extended travel time. Aside from the unforeseen trail mishap, nightly accommodations presented challenges of their own. The ever known presence of Mountain Lions, Bears and Wolves in the region gave cause to nights spent in trees, possibly tied to a bough to prevent falling out while in a slumber. In lieu of that, large fires were common place in an effort to discourage after hours visits from the predators and scavengers looking for an easy meal. Indians, while rarely troublesome, were always a foremost consideration. Nightly care of livestock may often have resulted in hobbling, or tying bells to the animal, or both, to ease the task of locating them if they wandered off or were spooked during the night.

As time passed, the road was widened to allow for wagon access and nightly accommodations became somewhat easier. As taverns sprung up, at one time every couple of miles, the weary traveler could at least get in out of the weather and acquire a warm meal or spirit. Still though, some available sleeping arrangements left much to be desired. Wagon travel of course had its own hardships. Broken wheels were common place traveling over unforgiving terrain, as was the ever present risk of getting stuck on a tall stump. Hence the phrase; "stumped". Wet areas provided particular hazards to the wagon master. Often ruts created by heavy loads would be deeper than your axel was high or the road so boggy, animals as well as vehicles would succumb to the depths of the mud. These areas would often be over laid with crisscrossed logs called corduroy to make them passable, though creating a somewhat uncomfortable ride.

River and stream crossing were an ever present obstacle. Ferries were present at the Ohio, Muskingum and Scioto Rivers as well as Wills Creek. A ford was used at the Hocking River until a bridge was built in the early 19thcentury. Both methods of crossing were inconvenient and could be quite dangerous in seasons of high runoff. Early ferries were simply planks attached to a couple of canoes, often only big enough for a man and maybe his horse. These were quickly replaced by flat boats providing more room and stability. Fords often had extremely steep banks making it difficult for travelers with wagon and team.

All of these obstacles combined proved less hazardous than risking life, limb, and possessions on the untamed waters of the Great Ohio.

Migration of a road

Before Zane's Trace could be completed, it began to migrate. The lack of survey would ultimately result in unreliable memories of where the original route was cut. Almost as soon as the Trace was cut, and before its length was finished, travelers began using it. As fallen trees and seasonal swamps dictated movement off of the original trail to circumvent these obstacles, the Trace began to migrate. Local land owners often took it upon themselves to improve the trace by either widening or applying logs in wet areas to create corduroyed section of road. In Putnam's letter to the Secretary of the Treasury, 5 Feb 1800, it was written "Col. Ebenezer Zane has in the course of the last year, caused the road from Wheeling to Limestone to be straightened, and otherwise improved by bridges…" By the time the first surveys of the area of the Trace were done in 1798, it is likely that the road had already been altered from its original course. While these alterations may not have been much in some areas, it can be presumed that other areas deviated considerably. Some of the surveys, post 1800, go as far as to note this migration showing Zane's "Old" Road and Zane's "New" Road on the same plat! On 13 Jun 1802, an act of congress enabled the people in the eastern portion of the Territory Northwest of the Ohio River to form a constitution and state government… This act entitled the State of Ohio to receive 3% of all land sales within its boundaries for use of road maintenance and improvement.

The largest migration of the road was due to an Act of the Ohio General Assembly in 1804. On 18 Feb 1804, at the second session of the State Assembly, an act was passed that resulted in a new state road divided into 16 parts, each with its own commissioner. Documents and surveys are rare but assessments of those available indicate this new state road was surveyed and became what would be the updated road system of Ohio. Through the next quarter century, as more state funding became available, roads were straightened and adjusted to be "useful and of public convenience".

As the route of Zane's Trace migrated, so did the name. As was common, the road was locally known by the name of an intersecting town. Depending on the area, names for Zane's trace may have been; Zane's Road, Chillicothe Road, Wheeling Road, Zanesville Road, Old Post Road or any combination thereof, plus a few others. As generations passed, so the various names passed also. Until locations of that original Trace were lost but to the records aforementioned and as the names and memories aged, the true route noted in history books may only be as accurate as the memories creating the content.

The first road west, despite the history and confusion, Zane's Trace remains as much of a piece of American folklore and as important as the Oregon or Santa Fe Trials of the Old West.

© Old Northwest Genealogy 2019

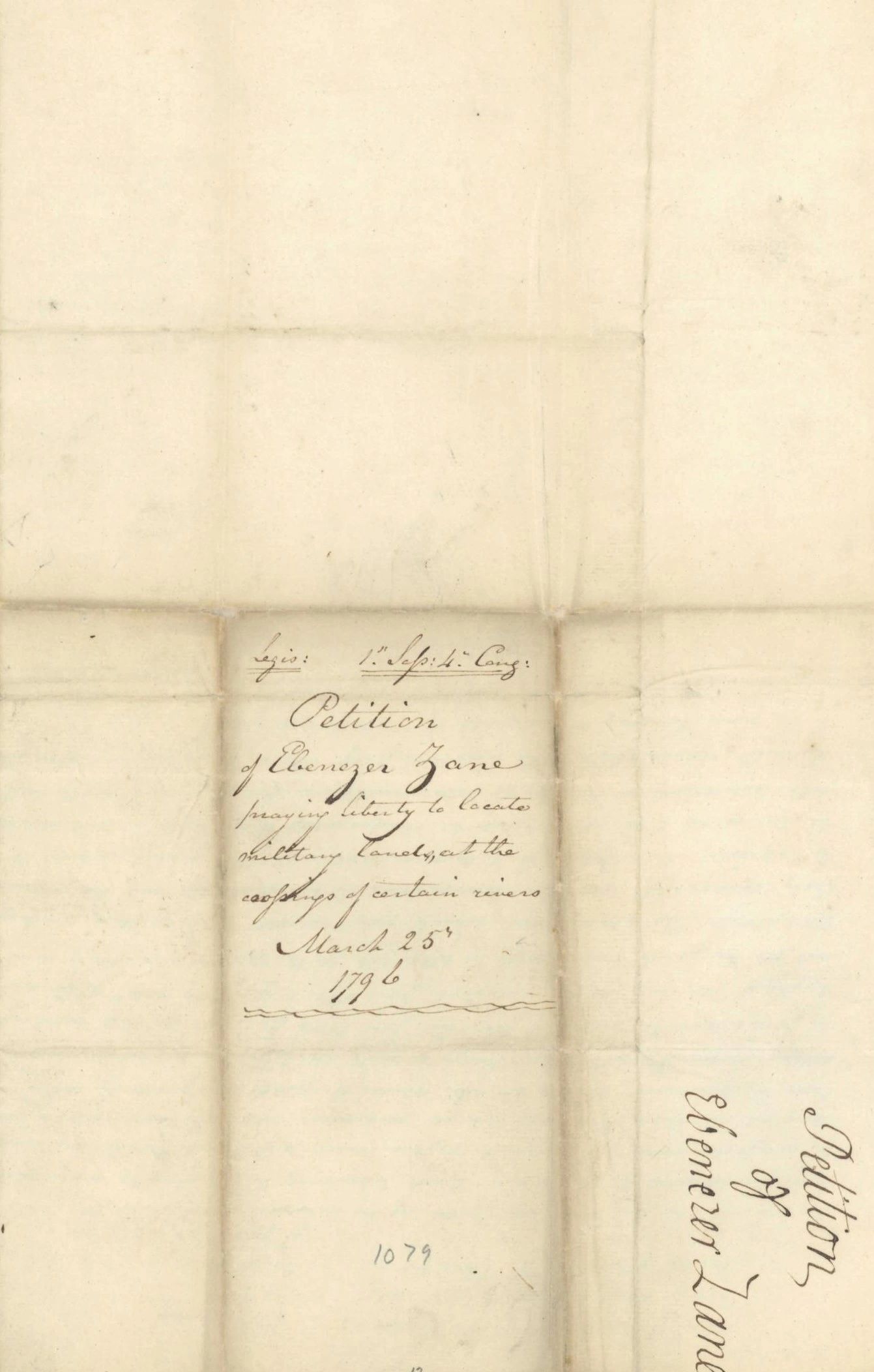

Zane's Petition

Zane's Patent

Land Districts crossed by Zane's Trace

maps

Migration of Zane's Trace

Belmont County

Guernsey County

Muskingum County

Perry County

Fairfield County

First land owners east of the Scioto River

Copyright © 2024 Old Northwest Genealogy - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy